- Home

- Margulies, Phillip

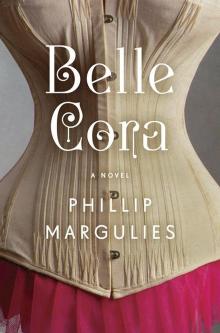

Belle Cora: A Novel Page 44

Belle Cora: A Novel Read online

Page 44

“Did they find out?” asked Mary.

“It seems they’ve given up,” I said in a disappointed tone, and we began looking for letters addressed to the several passengers whose mail we had agreed to retrieve. We made piles; there were many, more than we had money to redeem. Jeptha and I had four: one addressed to me, one for us both, and two for Jeptha only. His father had written him from Ohio. One letter had no return address: I recognized Agnes’s special round loops and capital “T”s. The letter for both of us was from Solomon Godwin.

I gripped these letters in my hand, and considered. Sometimes Mary talked to Jeptha. “The gall of this woman,” I said, waving Agnes’s letter.

“What? Who?”

“The woman Jeptha kept company with before me. She’s written to him, and has not put her name to it. If I didn’t know her handwriting, I would not have known, I might never have known. That is to say—I only hope he would have told me. Mary, might I ask you for a favor?”

She put a fist in front of her pursed lips and made a little gesture of turning a key. Begging her pardon, I crossed the room to read in the light of a deeply recessed window.

The letter that was addressed to me alone was from Anne. I expected it to contain news of Frank. If any mishap had befallen him, this letter would tell of it. For a moment, I stood judging myself. Exactly how bad a mother was I? Was I heartless enough to open my enemy’s letter to my husband before the letter that might inform me that my son had been bitten by a snake and died? I opened Anne’s letter first.

She knew it would be awkward for me to receive mail that Jeptha could not read, and had the elementary cunning to assure me first that everyone was well, and to congratulate me on my marriage and tell me other news, before adding, “Maybe you would like to know how Frank, the orphan you brought to us, is adjusting to his new home.” Then she described his growth and health and latest accomplishments and adventures in a detail that might be attributed to her own doting enthusiasm.

Perhaps it was disgusting of me in view of what I had done about Frank, the thousands of miles I was willingly putting between us, but in fact I hung on every word I ever received about him. I pictured him as he was when I saw him last: the dimpled elbows and the sweaty sweetness of his neck; his cries and babbling and chubby thighs. When Anne alluded delicately to his unnatural quietness in the first week after his arrival, I felt as sorry for both of us as if we had been separated by some tyrant’s decree and not my own free actions. I got a lump in my throat over the news that he was climbing stairs and going into closets. He had bent a silver fork double, such was his immense strength, and was not afraid of anything except all dogs other than the two family dogs. My baby, my boy, my little man!

I experienced all those thoughts and emotions without for a second forgetting the letter from Agnes. And at last I opened it.

Dear Jeptha,

I hope this letter finds you well. I would love for you to write and tell me, and it makes me sad to doubt you will. It seems improbable enough that you will even read this, but I will ask anyway the questions one asks: How are you? How is your journey? What is it like on the ship I was supposed to be on, that we were going to take to California together? Do you think of me? Can you imagine what it is like for me to sit at my writing desk picturing you and your new bride aboard the Juniper?

Do you sleep well, Jeptha, on the rolling waves, on the deep waters? I do not sleep very much. I weep, and I pray, and often during the daytime, on an omnibus, I nod for a moment or two, but I do not sleep. When I lay my head on the pillow your voice comes to me, usually uttering the last words you said to me, perhaps the last I will ever hear from you, all so deservedly harsh, and most of them quite true: yes, I deceived you; yes, for selfish reasons (though, you will certainly find out one day, and probably soon, my reasons were not entirely selfish, unless it is selfish to hope to prevent someone you love from doing himself a great injury). I deceived you, and you said that because of it you could never trust me again; I hope that isn’t true. You said I meant little to you now. I do not believe that is true. But I will mean more, the more you learn about her.

In the grip of your anger, you said that you can never again believe anything I say, but that is not logical: if I say the sky is up and Monday follows Sunday, you must believe me. Other propositions you can put to tests. Write to the Female Reform Society and ask them if Arabella Godwin is a member of their organization. They’ll tell you they never heard of her until I asked about her! Ask them if it has ever been their practice to place orphans in homes. They’ll tell you it has never occurred to them. Write to my mother, and ask her whom Frank resembles, whose child he obviously is: the little boy is Arabella’s child! Even Anne obviously knows, though she hides it to spare him the indignity of growing up as a bastard, as people would quite naturally and I suspect justifiably assume he is.

Ask your wife if she is the mother of a child whom she has abandoned. She will deny it, but I would love to hear you ask.

There’s obviously much more to unearth, and I will do my best in your service, Jeptha, whether or not you thank me for it. Perhaps she is still married to her first husband, who will not give her a divorce. In that case, your marriage to her is not valid, and you are under no legal obligation to her. I can imagine how difficult this is for you to read, but it seems unlikely that she has really amassed the money she has at her disposal as a dressmaker. Either one rich man has given it to her, or many men have given it to her. It is an ugly possibility, but consistent with her character. It must be faced.

Certainly, even if your marriage to her is technically valid, you have excellent grounds for a divorce.

Arabella, if it is you, and not Jeptha, reading this, you must realize how hopeless your position is in the long run. You can intercept one letter, but there will be more. Sooner or later, one will get through; and even if it doesn’t, he will see through you finally. You are one kind of woman pretending to be another. You are brass passing as gold. Every gesture, every word rings false. It has to. He will know I was protecting him. You can’t win.

Jeptha, you are my heart.

Your sister in Christ,

Agnes

I stood there, fearing the pain she would inflict on us should one of her letters reach Jeptha, yet certain that her lies (even to myself I called them lies; they were lies in spirit) could never destroy our love. Poor Agnes, my poor old enemy, was telling Jeptha about a woman who no longer existed. She could not know how changed I was, she could not imagine the delight we took in each other every day and night aboard that foul, musty, uncomfortable ship. Husband and wife, we had grown into each other, we were inextricably entwined and woven, turning Agnes’s collection of nasty facts into so much biographical trivia—into, at worst, a history of my misfortunes.

MY GRANDFATHER’S LETTER READ AS FOLLOWS:

Dear Jeptha and Arabella,

Greetings from New York. I expect that about now you are glad to have land under your feet and relief from the monotony of shipboard life. You may know from reading New York newspapers that the cholera is taking a terrible toll of life here. Sadly, there have been deaths in the families of my business acquaintances. We pray each night that Almighty God will show us greater mercy than we deserve.

While I hate to worry you when you are helpless to act, I must apprise you of disturbing news from the Pearson Academy, where Lewis boards as a scholar. Lewis is not there. He left, along with two other students and a man—we have reason to believe it is Edward—three days following your departure aboard the Juniper. From the testimony of other young men at the academy, it is clear that they mean to go overland to California. Perhaps it is only to be expected. They are young, and wish to “see the elephant.” I now regret opposing their desire, since they are undercapitalized for such a journey, and I would have seen to better preparations. If all goes well, they may arrive in California before you do. When you are in San Francisco, try to establish contact with them—I am hoping they will leave

some word in the post office there.

On another subject, I have been making inquiries here among New York and Boston merchants and importers who are setting up branches in San Francisco. They will receive letters in advance of your arrival and will expect your call. I append a list to which I will probably be adding more names later.

Write to us; we look forward to hearing of your adventures so far.

Sincerely,

Solomon Godwin

I decided to open the letter from his mother and father, in case Agnes had reached them with her suspicions or asked them to enclose a letter of hers in the same envelope with theirs. But, fortunately, she had not yet thought of that. The letter wished Jeptha luck in California. It did not congratulate him on our marriage but acknowledged it, saying that he was a smart man, so he must know what he was doing.

WE RETURNED TO THE CUSTOM HOUSE to find Jeptha arguing with his flock. He proposed to send George Ewell to find us a hotel; the others thought it was a bad idea, since this mission would take the young man past many purveyors of sin. Like one of the Bible’s timorous prophets, Ewell pleaded his inadequacy to the task. Jeptha gripped the drunkard by the shoulders and swore he was ready. I told Ewell that I, too, had faith in him, and added to his instructions various specific demands as to the cleanliness of the rooms and, in particular, the beds. He was to see for himself and not take the proprietor’s word.

A few hours later, still sober and godly, Ewell led us to a hotel. It was sealed off from the street with a high wall, with gardens around the central building, whose walls were climbed by vines, and another garden in a courtyard, and many broadleaf plants in pots, and cross-ventilation. A square, narrow, turning staircase rose up to our room.

Jeptha let me walk before him, as a gentleman should. Our previous couplings aboard the Juniper, with only the darkness for privacy, the repertoire limited by the slender berth, had been an experience sui generis, reminding me of no others. But now, as I walked before him, with Agnes’s letter fresh in my mind, I thought of all the times that I had mounted stairs with a man behind me, his eyes level with my hindquarters; and I felt as nervous as a virgin, though for the opposite reason. In the room there would be the freedom of a wide bed. I must not seem to know too much. As he prepared to open the door, I smelled his closeness, which I loved, but I remembered the smells of other men. This had always been an anxious moment, the seconds before I was alone with the stranger who was paying for the privilege of taking me to my depths, ransacking the most secret, forbidden chambers of the temple’s holy of holies and, if such was his whim, fouling it, because he could, because he had the price.

Then we were in the room, and I expected to examine it, to see if the bed was clean and firm, but as impatiently as any of my gentlemen in former times, my husband turned me and pulled me toward him. As if someone were flipping a deck made of a hundred face cards, all jowly kings and tumescent knaves, the visages of a hundred men passed before my mind’s eye while he stripped and unwrapped me, layer by layer, kissing each new patch of flesh as it was revealed, to claim it, to make it his. He lifted me. He took me to the bed, my Jeptha, whom I had known since I was a girl of nine, and his knees drove mine apart, and he bit my lips gently with his teeth, and he smiled down at me teasingly in a way that was at once cruel and compassionate, and what happened then was an exorcism, as, thrust by increasingly urgent thrust, he filled me up until there was simply no room left for anyone else. I felt as thoroughly claimed and possessed by this one man as I could wish. I was convinced that he had performed a magic rite which turned the world right side up again. We lay side by side. He stroked his face with my fingers. Then he rummaged through our bags and took out a jar of preserved plums, and I fed one to him and he fed one to me, and we licked each other’s fingers.

Later, he rebuked me, gently, for opening a letter addressed to him. I told him that I had had a premonition that it might contain bad news and I could not bear to wait. I admitted that my impatience was a great flaw in me. To change the subject, I asked him if his family thought he had married Agnes (his father’s letter had not mentioned my name). He assured me that they knew the facts and apologized for the tone of their letter. “They’ll come around, I hope.” He did not seem to be too sure of this, and added: “Anyway, who knows when we’ll see them again?”

DOWN BY THE SHORE, HALF-NAKED MEN sold fish out of canoes, and for two cents women who stood under large linen umbrellas would serve you a bowl of hot coffee or a stew of meat and black beans. We walked by heaps of outlandish fruit; green parrots; a small white monkey with a devil’s face; a giant rat in plate armor; stores with striped awnings; work gangs and soldiers; and a priest wearing about twenty pounds of black cloth and a black tricornered hat. This was Rio. We spent two weeks there, enjoying the honeymoon our swift departure from New York City had denied us. We saw cathedrals, forts, mountains, plantations, churches, and gardens, and learned the stories of natives and other travelers.

Every paradise has its serpent, however. Jeptha, chosen by the California Missionary Committee partly because of his strong Free Soil views, was troubled to realize that nearly all of the Negro laborers we saw in Rio were slaves. Each morning, their owners sent them out of doors to get money; when they returned, they must, in effect, pay their masters not to whip them. The rowers, the coffee carriers, the porters, street vendors, charwomen, maids, and cooks were all slaves; and the prosperity of Brazil rested on the sugar plantations of the interior, where men fresh from Africa were regularly worked to death because it was more economical to import new ones than to keep the old ones alive. Since cheap labor makes low prices, many of our incidental pleasures were implicated in these crimes. But we told each other we could not immediately perfect the world. Happy with the drugged irresponsibility of lovers, we did not feel this injustice keenly, just as we had not minded the bad water aboard the ship.

XLIV

BACK ON THE JUNIPER, WE RECEIVED the thrilling news that two stateroom passengers were languishing in a Rio jail. This meant that, with a little reshuffling and for a fee we were glad to pay, a whole stateroom might be free for Jeptha and me. But before we could rush to take possession of it, we were told that the stateroom had already been given to a woman and her son. She was French, a widow. Her name was Marie Toissante. The boy’s name was Philippe.

Philippe was eight years old, an active, healthy, intelligent child, curious about everything that went on aboard the ship; soon he became the pet of the passengers, who tousled his hair, gave him candies, played card games with him, and let him hold the fishing line. The boy followed anyone who interested him. His favorites were Jeptha and a tall, sandy-haired, round-shouldered fellow named Herbert Owen, who spoke French and was very happy to make himself useful to a handsome woman and her son. After a while, one saw that really Jeptha was the boy’s favorite, and Owen was being used as a translator.

I have not mentioned Herbert Owen until now since we saw little of him in Rio, but from our first weeks aboard the Juniper, he was the person whose company we best enjoyed. He was twenty-eight years old—one of the oldest passengers—from a good old Boston family. About a year earlier, his reading of German philosophers had turned him into an agnostic, which did not stop Jeptha from liking him. In fact, I could not help but notice that Jeptha’s efforts to change Owen’s mind were rather feeble, as if he did not want to spoil him. For Jeptha, Owen was a relief from some of the pious men who treated the pastor as their very own private property. He was gentlemanly and cultivated; he had traveled, had studied the law and practiced it briefly. For Owen, who knew himself to be a dilettante and a tourist, untested by life, indifferent to ideas—his freethinking was just a toy—Jeptha was someone with convictions, an enviable and admirable trait.

Owen agreed to attend Jeptha’s Sunday services on the quarterdeck if in return Jeptha read Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason, famous in our day as a Deist tract. Jeptha read it openly, high in the rigging or on his back on the deck. When people a

sked him about it, he told them of his bargain with the agnostic, and said that it was never good to suppress a mistaken book: one must read it to refute it. Book burning was for priests, not ministers. The Gospels need not fear a fair fight.

He believed this in the face of powerful countervailing evidence, as I learned one day when he was twenty feet above me on the mast; the book slipped and fluttered down open, like a gunshot bird, and I caught it. I remarked that Owen and his friend the devil would be grateful to me for saving their book, and Jeptha said, “This isn’t Owen’s copy.”

“Oh?”

“Look on the flyleaf,” said Jeptha.

I looked. In the tropic heat I felt a chill: “Ex Libris: William Jefferds.”

Climbing down to retrieve the volume, Jeptha informed me: “His name is also on the flyleaf of Voltaire’s complete works, and he had a book by another Frenchman, Volney, who says that all religion is one, and a Life of Jesus which tells the Gospel story without miracles, and some reviews of German books which try to prove by Hebrew grammar that God did not write the Scriptures. I saw some of them when I was still in Livy. He said he read them to refute them, but I should wait to read them until I was older.”

I returned The Age of Reason.

“How did he refute them?”

“He didn’t,” said Jeptha. “They convinced him.”

That night, we slept on the deck in our clothes, holding each other, lit by the stars of the Southern Hemisphere, cooled by a steady breeze, enjoying an experience common to drunks and children: our bed was in motion, conveying us to dreamland. And Jeptha told me that Jefferds had lost his faith many years before he died. It was in his diary.

Belle Cora: A Novel

Belle Cora: A Novel