- Home

- Margulies, Phillip

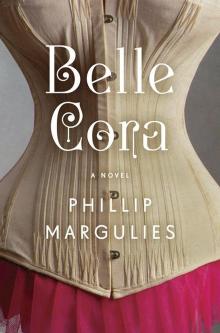

Belle Cora: A Novel Page 28

Belle Cora: A Novel Read online

Page 28

“What do you mean? Where are we going? Where are you taking me?”

“To yer brother! Lewis! You’ll be wanting to see yer brother, won’t ya?” Under the lisp, she had a brogue as heavy as Mrs. Shea’s.

She took me down the staircase, which had one turn in it, into a basement with a low ceiling and many beds: some on legs; more in shelflike tiers, one atop another, set in the walls, canvas hammocks strung between two wooden rails. There were also straw mattresses on the floor. I could imagine how crowded this place would be when night came, and how dear unconsciousness would be then. The air stank, like all the air of the neighborhood, but with mildew, vomit, and drink added to the usual aromas of sewage and rot. On the walls near the floor were wavy stains of varying hues, the geological record of yesteryear’s floods.

There were only a handful of men in the wretched room now, most of them pickling in liquor, yet still the girl had to point my brother out before I saw him. He was like everything else here, a chaos of muddy hues. Then his name was torn from my chest—“Lewis! Lewis!” I spoke it not so much to alert him to my presence as to conjure him into continued being, and I ran to him, still crying his name. I saw when I stood over him that I had been right to come. He had been cut badly in at least two places, with bandages around a wound at his waist and others around his right arm, and he was sick, very sick, from the festering of his wounds, and this was no place for him to recover. But I could see that someone was taking care of him. The bandages, though less clean than we like bandages to be today, had been changed recently, and the bedclothes were clean and dry. “Belle,” he said wonderingly, when he saw me, and then he told the skinny prostitute that I was his sister. A few seconds passed, and he added, “That’s Bridget, Belle.”

“Lewis,” I said. “Lewis, I was at our old house.” Quite unexpectedly I began to weep. “I was in Bowling Green today, Lewis. I was there just now. In Bowling Green.”

XXIX

I WAS GLAD THAT SOMEONE HAD HELPED my brother, grateful—but I was also dismayed, more than I can express, more than I can really remember now, to find myself under an obligation to a gap-toothed prostitute. She had changed his clothes, bedding, and bandages, and brought him clean water, and broth that she had paid for with her own money, earned through the degradation of her body. Perhaps she had saved his life. I realized all that, and yet I felt invisibly damaged just by being in her presence. People would think differently of me if they learned that I had been here and had touched her hand.

We sat on the edge of an empty bed and talked through the snoring of men who looked as pale as if they had their drink delivered here and the sun’s direct rays never touched them. In the most offhand way, she told me things no decent woman should know; and, fearing that no woman could remain entirely decent once she knew them, I listened. She said she had a room to herself in the brothel that occupied the second and third floors of the house, and she took care of my brother when she could. She had wanted to take him into her room—most of her clients wouldn’t have cared—but Mrs. Mulrooney would not allow it; she did not want someone dying in the house.

I didn’t know where to look, every view was so disgusting. At last, for lack of an alternative, I chose Bridget’s homely face. “I must get him out of here. I’m scared to walk around this neighborhood alone.”

“I’ll go with you,” she said cheerfully.

While we were together, she told me more about herself. She told me what she liked and didn’t like. She liked whiskey, rum, chocolate, hot buttered corn, the theater, Shakespeare, and the actor Edwin Forrest. She liked dancing. She liked New Jersey—it was beautiful. She liked Yankee Sullivan, the prizefighter. She liked the policeman Tim O’Hara, who had helped her and asked for nothing in return. She did not like Pell Street, where something bad had happened to her that she decided not to talk about. She didn’t like what men and women did in bed. Did anyone really like it? She didn’t believe even the men really liked it. They just thought they had to do it because they were men.

She told me how she had become a prostitute. She had been born in County Waterford. Her parents died. With the help of her landlord, who wanted to get rid of his indigent tenants, she came to America, and she sought out her aunt Liz, a widow. Aunt Liz was living in a small apartment with three young women who took turns taking men to the one bedroom in the apartment; they paid Aunt Liz for the use of the room. Sometimes the girls served two or three men in the room at once. Soon after Bridget arrived, her aunt kicked out the three girls, to Bridget’s relief, but then started bringing men to Bridget, saying that she had to earn her keep and she wouldn’t be sorry, it was a good life. “You’re sitting on your fortune,” her aunt said. Bridget wept and resisted. Her aunt threatened to kick her out to roam the streets, where, Aunt Liz said, she would certainly become a whore anyway; finally, Bridget gave in.

A year later, when she was fifteen, she had left her aunt so that she could keep more of her earnings. By now she was used to the life. It was all she knew, and not so bad. She had all her meals out. A maid did all the cleaning and washing for the girls. Bridget spent far more time standing and waiting than she did in the performance of her duties, and she had money for oyster saloons and ferryboats and theater tickets, and for a drop of whiskey now and then. Even so, sometimes she felt blue, because this was not the life she had planned; of course, it was different for someone like me (I learned gradually from such parenthetical remarks that she thought I was a whore, too, but a fine one, far above the likes of her). She planned to quit any day now. I didn’t ask, but she told me that her price was a dollar. She thought that was fair, since she was, she admitted, “no Cleopatra.” It could go lower if there was haggling.

When I told her that I worked at a mill, she apologized for her mistake and asked me if it was true that, as she had heard, mill girls had to grant their favors to the bosses. I told her it wasn’t true. I could tell she didn’t believe me.

I WENT TO SEE THE WIDOW mentioned by Mrs. Shea; she had no room, but knew of another widow, Mary Donovan, on Mulberry Street, who was looking for lodgers and who, for an additional fee, would probably wash our clothes and feed us.

She lived on the fifth floor of a five-story brick tenement that had been built by an enterprising landlord in the courtyard surrounded by his other properties. To reach it, we walked through an alley past sacks of refuse and stray cats. A skylight was the only source of illumination on the stairs, which were in the center of the building, a squarish spiral with an empty square drop in the middle. A small girl sat on the steps between two floors, playing with a whirring, buzzing toy made out of a button and a piece of yarn. She ignored us as we passed. I heard her coughing, and looked back in time to see her put down the toy and cough into her hand and look.

When I knocked at the door at the top, I was met by Mrs. Donovan, who had the permanent squint and roosting buzzard’s posture which I later came to recognize in women I saw on the street as the mark of the seamstress. I explained my situation, and she explained hers. She had been widowed for about a year. She had six children, boys and girls. Three of them were out picking rags or sweeping streets. One was being watched by a neighbor down the hall. Two of them, girls, were right here, making shirts, with terrible urgency and concentration.

In the apartment below us, a man screamed, “Get up, you drunken slut!” amid words I could not make out, and “My dinner! My dinner!” The voice was passionate, as if his poor dinner lay brutally slain and he was mourning it and demanding justice. A child cried. A woman spoke. Later, when we were discussing the room, we heard thuds and grunts, and Mrs. Donovan observed calmly, “Now he’s beating her.”

It was horrible, but I returned that evening knowing it was the best I could do on short notice. It was only temporary, after all. We had to live in New York while I tended to Lewis, and we had to live cheaply until I got a job.

Incredibly, Lewis was reluctant to leave 160 Anthony: he said that that was where Jocelyn would come looking for

him. He loved her; he was going to forgive her and, if there was no other way, marry her; they’d put what she had done behind them. I told him that we would leave word where we had gone, and that I had come here to find Jocelyn as well as to take care of him. We would find her, and we would take her away from that place.

I managed to persuade him, and we went to live on Mulberry Street, the two of us in the cramped little room that had belonged to the two homely daughters, who moved into another room already occupied by their mother and their youngest brother. The three remaining brothers slept in the kitchen.

Mrs. Donovan spent a surprising amount of time on her knees beside a pail, weilding a rag, with indifferent results. The portion of the walls beyond her reach were so smutty that if I stood on a chair I could write my initials with my fingernail. The cracked plaster ceiling was brown with the greasy residue of smoke; and whenever I think about that tenement, I always remember the dreadful stench that came through the windows if you were foolish enough to open them under the misapprehension that nothing could be worse than the air inside. I thought the air might actually be poisonous. In a week or two perhaps, Agatha and Elihu would receive word that I had been fired from the mill. What would they think and say? I thought of Agnes, living respectably with her parents until she married some weak-willed man with good prospects—that wooden doll George Sackett, perhaps. I thought of Jeptha, living in his father-in-law’s residence, or with his unspoiled wife in a boarding house, as many married couples did in those days. Maybe he had his own house already. If only he could see me now, I thought, feeling that I had reached the depths of degradation and it would be a great rebuke to him.

ON THE FIRST NIGHT WE SPENT IN OUR ROOM on Mulberry Street, Lewis’s fever worsened. He shivered and sweated. There weren’t enough blankets for him. I felt so helpless that I prayed. I plied him with patent medicines, changed his bandages, and fed him meals of bread and soup from a nearby oyster house. Gradually, he began to gain strength, and one day he said he was all better; it was time for us to find Jocelyn, as I had promised. I looked away while he got into his trousers. Then I heard him stumble; when I looked back, he was sitting on the floor.

“Give it a little more time,” I told him, and he got back into bed. In a day or two, he did seem much better, and I told them that I had an idea of how we could begin our search for Jocelyn. I had been thinking about Mrs. Shea’s advice regarding Con Donoho, Sixth Ward street inspector, and his grocery on Orange Street, one block below the Five Points intersection. Donoho was a power in the neighborhood, she had said. I thought that if I mentioned Mrs. Shea to him, perhaps he could help us find Jocelyn.

“We’re going to ask about Tom Cross, too,” I said, mainly in order to see the look on Lewis’s face when I did. There was something between Lewis and Tom that I did not understand. Whenever we talked about Tom, Lewis was evasive and looked uncomfortable. “Tom is sneaky,” Lewis had said a few times when I was tending him in our room. “He likes to get a handle on people.” He said it as if the mistake had not already been made and Tom’s bad character was not already well established. I remembered the day at the Harmony boarding house when they had been bragging of their exploits on the canal and Tom said that Lewis could do harm if he was of a mind to; that he was a killer. Whatever it was that worried Lewis so much, it had probably happened before they’d come to New York City.

We went up the stairs of the Donoho grocery Indian-file, because most of the space on each step was taken up by a barrel overflowing with brooms, or charcoal, or herrings. Inside, the idea of a drinking saloon and a grocery contended, with no decisive outcome. Besides cabbages, potatoes, eggs, flour, candles, soap, and coal, there was a handsome bar well stocked with liquor, as well as a crock of tobacco and a rack of clay pipes; a sign said that whoever bought a shot of whiskey was entitled to an ounce of tobacco and the temporary use of a pipe.

Mrs. Donoho, behind the bar, was dispensing beer into a bucket, which she handed to a boy of about eight. Then a man asked for a pound of salt pork. When she went to get it for him, he said, “Not that barrel.” She told him, “You’re too suspicious,” and got the meat from another barrel and wrapped it in newspaper, and finally she turned with a big smile and hard eyes to us. She was squat, pale, and sweaty, with strands of her thin hair pasted to her brow. When I mentioned Mrs. Shea, her manner softened. When I said we were looking for a girl named Jocelyn who we believed was working in a house of ill fame, she said, “A house, do you say, of ill fame? I’m sure I don’t know about such places, if indeed there are any hereabouts.”

She spoke loudly. There was laughter from men and women within earshot.

“We thought, as many men come in here, and men will be men, you might ask if they have heard about a girl with that name,” I said.

“How do you vote?” Mrs. Donoho asked Lewis.

“I’m not old enough to vote yet,” said Lewis.

“What a pity. Still, there are other ways to be useful come election time,” said Mrs. Donoho, looking right and left, and there was amusement again. “Come March if you’re still here, speak to Con about it.”

“I will,” said Lewis.

“And I will ask about your poor friend Jocelyn,” said Mrs. Donoho. “I do hope she sees the error of her ways. Is she handsome?”

“She’s beautiful,” said Lewis. “But young. She’s only fourteen, and looks younger.”

“Well, I’ll tell you, I’ve heard about such places, things one shouldn’t hear, but folks tell me for the pleasure of seeing me blush, and I’ve heard that some of them make a point of offering young women, children practically, to men who are shy with grown women. If I were a man and could go safely into such places, I would look there. I wouldn’t look around the Sixth Ward.”

Lewis asked her about Tom Cross.

“I don’t recall a man of that name,” said Mrs. Donoho. “Does anybody here know a Tom Cross?” she asked generally, and no one seemed to know.

“He might be known by other names,” said Lewis, and he described Tom, naming his profession and his fire brigade, while I watched Mrs. Donoho’s face.

Soon after we had left the grocery, and were blinking and squinting in the sudden brightness of the day, a man in a patched coat came up, tipped his shapeless hat to me, and dragged Lewis by the elbow a few yards away.

As a result, I was left standing alone. People of various types passed by. Often men turned to examine me. Two homely young missionary women came by, of the sort who stood outside drinking saloons and brothels telling the men who went through their doors to be ashamed, and to think of the little ones starving at home. One of them put a tract into my hand, and they moved on. Then, a well-dressed man tipped his hat and said I looked lost, and he would love to help me if I would let him. No, I said.

“It’s a lovely day. Wouldn’t it be fun to take a walk? Walk with me.”

“No. Please, leave me alone.”

“Oh, don’t be that way. I would make it worth your while.”

“You have made a mistake,” I said. “Here’s my brother.”

Lewis, whom I had seen give the man with the patched coat a coin, probably in payment for his information, was approaching. The man who had been annoying me tipped his hat again and left us.

“Who was that?” asked Lewis.

“No one. Never mind.”

Lewis contemplated the departing figure as he told me of his conversation with the man in the patched coat, who, it seemed, had overheard our talk in the grocery, and was now waiting halfway down the street. “He says Mrs. Donoho might help us find Jocelyn, but all she’ll do about Tom is tell him we’re after him. Donoho’s in with Alderman O’Daniel, and Tom paid O’Daniel to get him a job. Paid him with my money, and money he got selling Jocelyn to a madam. Because that’s what he did, he sold her.”

“What was the job?” I asked.

Lewis grinned the special, crooked grin of a person who is about to wise you up. “He’s a policeman. That’s how they g

et hired, all of them.”

“It can’t be true,” I said, but by the time I had finished denying it, I believed it.

We were naïve enough so that the foul streets looked more wicked to us, every brick and board of them, as we walked home in the knowledge that Tom Cross was a copper, and that every policeman one saw had obtained his job by means of a bribe.

We went home, and I cooked. When we were eating, I thought of something funny to say. “No wonder he’s so hard to find.” Even though a half-hour had passed, Lewis understood I was talking about Tom’s being a policeman, and he laughed, and the laugh turned into a cough, and the cough got out of control.

“Stop it, Lewis,” I said. “Don’t get sick.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, but he went on coughing, one of those complicated, percussive coughs that call to mind factory noises—machines in his chest manufacturing some unpleasant fate for us both. He spat into his handkerchief, cleared his throat one more time—his little chest sounded cavernous, a vast chamber full of echoes—and spat again. I insisted on examining the sputum.

“My God, Lewis,” I said, for it was green. I did not know why, but I knew that whenever my mother had seen green in her sputum it was a cause for worry. From living in the orbit of her sewing circle—in that other life, in the house where now Mrs. Shea took in boarders—I knew some of the medical theories prevalent in those days before consumption became tuberculosis, before Dr. Koch and his pet bacilli. We believed that you inherited a predisposition to the illness, like a seed, but the seed might remain dormant in you, unless and until you received a shock to the system. A shock was like water on the seed. Should Lewis prove now to have consumption, I would attribute it to his having been knifed in the arm and the gut by Tom Cross.

Belle Cora: A Novel

Belle Cora: A Novel